Why these two budgeting methods are everywhere right now

If you’ve ever googled “how do I actually start budgeting without going crazy?”, you’ve probably seen the same two systems popping up over and over: zero-based budgeting and the 50/30/20 rule.

They both promise control, less money stress, and a clear plan. But they feel very different in real life.

Let’s skip the theory and walk through how each method really works day‑to‑day — and how to choose the one that actually fits your lifestyle instead of fighting it.

—

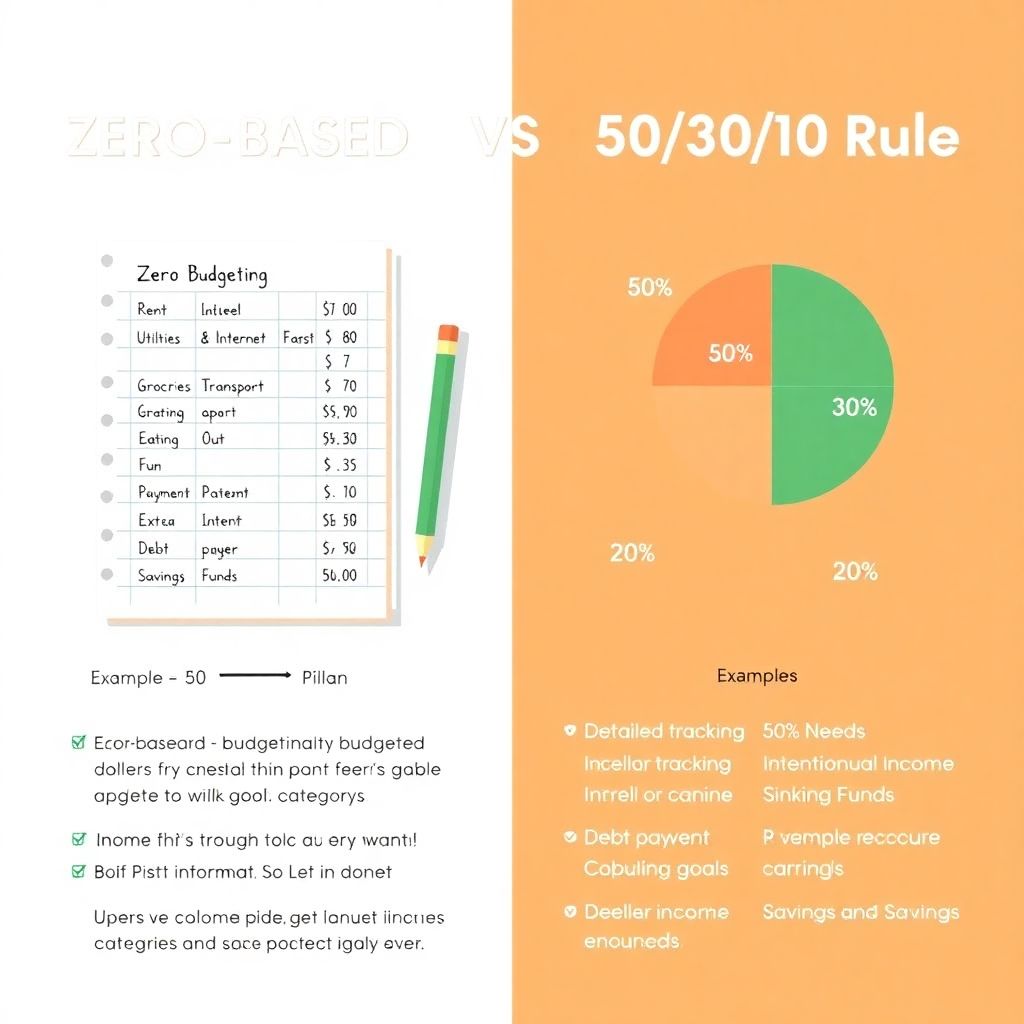

Quick overview: zero-based budgeting vs 50 30 20

In plain English:

– Zero-based budget:

Every single unit of your income is assigned a job: spending, saving, debt payoff, investing, whatever — until there’s literally “zero” left unassigned. Not zero in your bank account, zero in your plan.

– 50/30/20 rule:

You split your take-home pay into:

– 50% — *needs* (rent, bills, groceries, minimum debt payments)

– 30% — *wants* (restaurants, subscriptions, travel, upgrades)

– 20% — *financial goals* (extra debt payments, savings, investing)

They’re both trying to answer the same question: “Where should my money go?”

They just give you different levels of structure and detail.

—

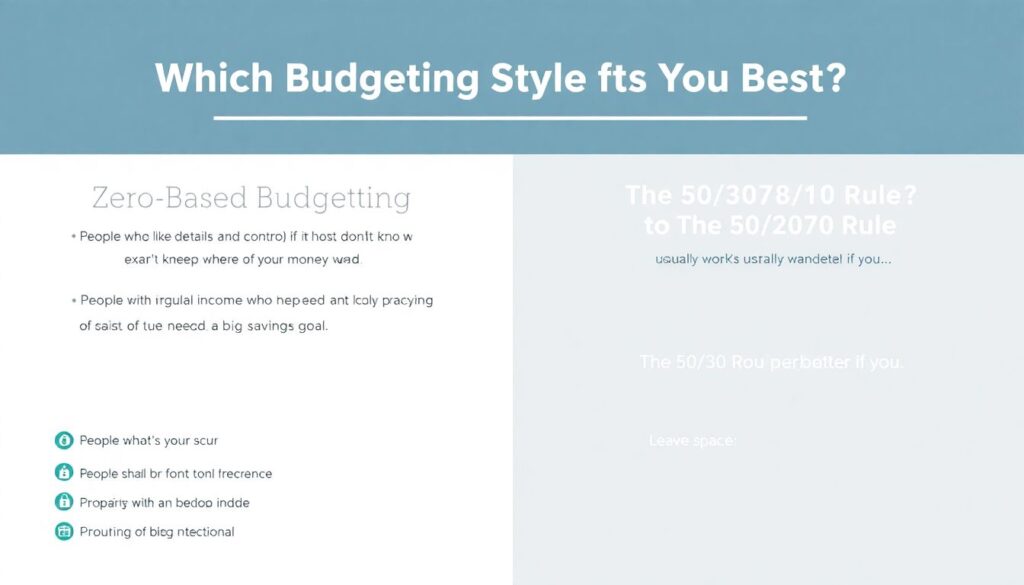

Who usually loves each method

Zero-based budgeting often clicks with people who:

– Like details and control

– Feel anxious if they don’t know exactly where the money went

– Have irregular income and need to be very intentional

– Are attacking debt or a big savings goal aggressively

The 50/30/20 rule usually works better if you:

– Want something you can understand in five minutes

– Hate tracking every single transaction

– Have relatively stable income

– Just want a simple guardrail so you don’t overspend

Neither is “better” in an absolute sense. The best budgeting method for beginners is the one you’ll actually stick with for more than two weeks.

—

How zero-based budgeting really works in practice

At its core, zero-based means:

> Income – Plan = 0

You decide in advance what every unit of income will do for you this month.

Say you bring home 3,000. You might plan:

– 1,200 – rent

– 300 – utilities & internet

– 350 – groceries

– 120 – transport

– 200 – eating out

– 150 – fun/entertainment

– 200 – debt extra payment

– 300 – savings

– 180 – sinking funds (gifts, car repairs, etc.)

Total: 3,000. Nothing “left over” unassigned.

Your bank balance doesn’t have to hit zero — your *plan* does.

—

How to start a zero based budget step by step

You don’t need an advanced spreadsheet or perfect discipline to start. You need one decision: “I will tell my money what to do before I spend it.”

Basic setup:

1. Calculate your real take-home income

Monthly salary after tax, plus side gigs, benefits, predictable bonuses.

2. List all your fixed expenses

– Housing

– Utilities

– Minimum debt payments

– Insurance

– Subscriptions

Be brutally honest. Don’t “forget” the gym just because you wish you didn’t pay for it.

3. Estimate variable expenses

Groceries, gas, eating out, small shopping, “I’ll just grab a coffee” money.

4. Choose your priorities

What matters *this month*? Debt? Emergency fund? Saving for a move? You can’t prioritize everything at once.

5. Assign every unit a job

Start with fixed needs → then minimum debt → then your top financial goal → then “wants” with whatever is left. Keep adjusting until income – spending – saving – debt payoff = 0.

6. Track and adjust weekly, not daily

Once a week, check:

– What did I actually spend?

– What category is about to blow up?

– Do I need to move money from “fun” to “groceries” or from “shopping” to “gas”?

You don’t “fail” if things shift. You just rewrite the plan and keep the total at zero.

—

Practical tricks to make zero-based budgeting less painful

Zero-based can feel intense at first. These techniques make it more livable:

– Use broad categories

Instead of 20 tiny buckets (“coffee”, “snacks”, “books”), try:

– Food at home

– Food out

– Transport

– Personal/fun

It’s still zero-based; just easier to maintain.

– Add a “chaos” category

A small “misc/unknown” line (even 3–5% of income) absorbs surprises so they don’t wreck your plan.

– Budget by paycheck, not by month

If aligning everything to a calendar month confuses you:

– Each paycheck gets its own mini zero-based plan

– You know exactly what this paycheck needs to cover until the next one

– Automate what you can

– Automatic transfers to savings right after payday

– Automatic debt payments

Then your zero-based plan becomes “default behavior” instead of constant willpower.

—

When zero-based budgeting is a bad fit

There are cases where zero-based budgeting might backfire:

– You consistently feel guilty if you overshoot a category by a small amount

– You already struggle with perfectionism or financial anxiety

– You know for a fact you hate tracking and will stop after a week

If the method makes you quit budgeting entirely, it’s the wrong method *for now*, no matter how “optimal” it looks on paper.

—

The 50/30/20 rule in real life

Now let’s flip to the simpler option. The 50/30/20 rule is a framework, not a detailed map.

Here’s how your 3,000 take-home might look:

– Needs (50% → 1,500)

Rent, basic groceries, utilities, minimum debt payments, essential transport.

– Wants (30% → 900)

Eating out, shopping, nicer-than-necessary groceries, Netflix/Spotify, hobbies.

– Goals (20% → 600)

Extra debt payments, emergency fund, retirement, future big purchases.

You’re not assigning every individual transaction. You’re just asking:

> “Overall, am I roughly staying inside these ratios?”

—

How to actually use 50/30/20 without overthinking it

Here’s a practical approach:

1. Figure out your true net income

Same as with zero-based: what actually hits your account?

2. Run a quick split

– Needs = 0.5 × income

– Wants = 0.3 × income

– Goals = 0.2 × income

3. Audit your current spending

Look at the last 1–2 months and roughly categorize:

– Housing, bills, basic groceries, minimums → Needs

– Non-essential upgrades, eating out, entertainment → Wants

– Savings, extra debt payoff → Goals

4. Spot the trouble zone

You might find:

– Needs > 60–70% (housing too expensive, debt too heavy)

– Wants > 40–50% (lifestyle creep)

– Goals < 10% (you’re spinning in place)

5. Choose one adjustment at a time

For example:

– Cut “wants” from 40% down to 35% for three months

– Increase “goals” from 10% to 15%

Small, realistic shifts beat big, unsustainable cuts.

This rule shines when you just want a compass pointing you away from lifestyle inflation and toward actual progress.

—

Using tools: calculators and apps that save you time

You don’t need to do all of this on paper. A few time savers:

– 50 30 20 budget calculator online

These are great for:

– Quickly checking if your rent is swallowing your “needs” portion

– Testing “what if” scenarios (new job, moving, paying off a loan)

– Seeing how far your current spending is from the guideline

– Budgeting apps for zero based and 50 30 20

Many apps let you:

– Set up proper zero-based categories with envelopes or buckets

– Or use high-level 50/30/20 “buckets” and just watch the percentages

– Sync transactions automatically so you’re not typing every receipt

Pick a tool that matches your attention span. If you hate data entry, choose an app with auto-import. If you’re privacy-focused, a simple spreadsheet or notebook is still fine.

—

Pros and cons from a practical standpoint

Let’s stay concrete and talk about everyday life, not theory.

Zero-based: what’s great

– You know *exactly* where your money is going

– Easy to prioritize aggressive goals (debt, savings, investing)

– Ideal if your income is irregular — you rebuild the plan each time

– You can see quickly when something doesn’t fit your reality anymore

Zero-based: the downside

– More effort and regular check‑ins

– Can feel rigid if you like spontaneity

– Higher risk of “I messed up the plan, so I’ll just stop completely”

50/30/20: what’s great

– Very simple mental model

– Easy to explain to a partner or friend

– Still pushes you toward saving/investing without being extreme

– Takes little time after initial setup

50/30/20: the downside

– Ratios may not fit high-cost cities at all

– Doesn’t force you to see exactly *what* you overspend on

– Easier to “cheat” yourself:

“Is this a need or a want? Well… I needed that new phone, right?”

—

How to choose: questions to ask yourself

Instead of asking which system is “objectively best”, ask:

– How much time per week am I honestly willing to give this?

– < 15 minutes → 50/30/20 is more realistic

- 30–60 minutes → zero-based can work

- Do I currently feel out of control, or just a bit unfocused?

– Out of control → start with zero-based for 2–3 months

– Slightly unfocused → 50/30/20 might be enough

– Is my income steady or all over the place?

– Irregular → zero-based by paycheck is usually stronger

– Steady → both methods can work, pick by personality

– Do I need strict rules or light guidance?

– If rules feel comforting → zero-based

– If rules feel suffocating → 50/30/20

Your temperament matters as much as the math.

—

Hybrid approach: you don’t have to marry just one method

You can absolutely mix them.

One practical combo that works for many people:

– Use 50/30/20 as your big-picture ceiling

– Try to keep “needs” under 50–55%

– Cap “wants” at ~30–35%

– Aim for at least 15–20% toward goals

– Inside those limits, use a light zero-based plan

For example:

– “Wants” (900) → pre-split to restaurants, entertainment, small shopping

– “Goals” (600) → pre-split to emergency fund, investment, extra debt payment

You’re borrowing the simplicity of 50/30/20 with the focus of zero-based — without going full spreadsheet warrior.

—

Common beginner mistakes (and how to avoid them)

People often quit budgeting not because the method is bad, but because expectations are unrealistic.

Typical traps:

– Underestimating “annoying” categories

Gifts, car repairs, pharmacy runs, random home stuff.

Solution: add small “sinking funds” in a zero-based budget or treat them as part of “needs” in 50/30/20.

– Trying to be perfect from day one

The first 2–3 months are data collection, not a final exam. You’re learning your real numbers.

– Ignoring your calendar

Birthdays, travel, annual bills. If you don’t look at the month ahead, every surprise feels like failure.

– Changing everything at once

Better:

– Month 1–2: just track and roughly follow the chosen method

– Month 3: adjust categories or ratios

– Month 4+: push savings/debt harder once you understand your baseline

—

Which method is more “beginner-friendly”?

If you’re completely new, overwhelmed, and just trying to not be broke at the end of every month, then:

– 50/30/20 is usually the *easier* starting line

– Zero-based is usually the *faster* transformation tool once you’re ready to get detailed

So the best budgeting method for beginners often looks like:

1. Start with 50/30/20 for 1–2 months to:

– Get used to watching your money at all

– Notice your personal spending pattern

– Build the habit of checking in

2. Move toward zero-based (or a hybrid) when:

– You want to speed up debt payoff or savings

– You’re ready for more precision

– You’re curious where, exactly, your money escapes

—

How to pick your method today and actually begin

To make this practical, decide now:

– If you want simple and fast:

– Google a 50 30 20 budget calculator online

– Plug in your monthly take-home

– Compare suggested numbers to your current spending

– Choose one specific change (e.g., cut wants by 5% and move it to goals next month)

– If you want maximum control:

– Write down next month’s expected income

– List all expenses + goals

– Build your first zero-based draft (it will be wrong; that’s fine)

– Do a 10-minute review each week, adjusting categories as reality hits

Both paths are valid. What matters is that you move from “I hope this month works out” to “I have a plan for this month.”

—

The real goal behind any budget

Whether you choose zero-based, 50/30/20, or a hybrid, remember:

The point is not to restrict every joy. The point is to stop accidental spending on things you don’t actually care about — so you can *deliberately* spend on the things you truly do.

Pick the method that helps you do that with the least friction. Then stick with it long enough to see the first real wins: a smaller debt balance, a growing savings account, or simply a month where money isn’t a constant background worry.