Budgeting for Beginners: A Practical Guide to Cash Flow

Historical Background (Историческая справка)

Before “budgeting for beginners” became a trending phrase on social media, budgeting was a strictly institutional tool. Governments and large corporations used budgets to allocate scarce resources, forecast revenues, and control expenses. The term itself comes from the Old French “bougette” — a small bag or pouch, essentially the container for money and records.

In the 20th century, as consumer credit, mortgages, and mass-market banking expanded, budgeting slowly migrated into personal finance. Early personal budgeting was mostly pen‑and‑paper: envelope systems, ledger books, and handwritten cash-flow logs. People literally labeled envelopes “Rent,” “Groceries,” “Savings” and divided their paychecks accordingly.

Today the concept is the same, but the tools are digital. The logic of corporate cash-flow statements — inflows, outflows, and net balance — has been adapted into every modern personal budget planner for beginners: spreadsheets, apps, and online dashboards that track money in near real time.

Basic Principles (Базовые принципы)

Cash Flow: The Core Concept

Cash flow is simply the movement of money in and out of your life over a defined period (usually monthly). Inflows are your salary, side hustle income, benefits, or transfers in. Outflows are rent, subscriptions, groceries, debt payments, and every coffee swipe.

A personal budget is a structured cash-flow plan. Instead of waiting to see where the money went, you tell it where to go in advance and then compare plan vs. reality. Think of it as a lightweight financial control system, not a moral report card.

Key Budgeting Principles in Plain Language

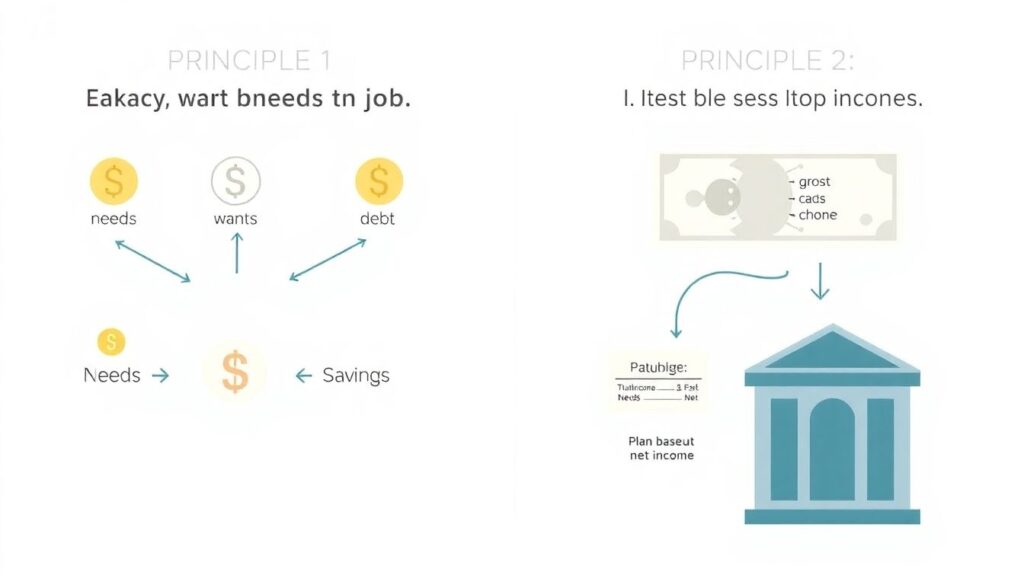

1. Every unit of currency needs a job

This is the “zero-based” idea: assign each dollar to a category (needs, wants, savings, debt) before you spend it.

2. Plan based on net income, not gross

Your usable cash flow is what hits your account after taxes, social security, retirement deductions, and insurance.

3. Separate fixed, variable, and irregular costs

– Fixed: rent, insurance, minimum loan payments

– Variable: food, transport, utilities

– Irregular: annual subscriptions, car repairs, gifts

This classification makes your cash-flow predictions far more accurate.

4. Expect reality to differ from the plan

Budgeting is an iterative process. You design, test, adjust. The first months are calibration, not failure.

5. Automate where possible

Transfers to savings, debt overpayments, and bill payments can be scheduled. Automation turns intention into default behavior.

How to Create a Budget Step by Step

If you want a concrete walkthrough of how to create a budget step by step, use this simple workflow:

1. Measure your current cash flow

Pull the last 1–3 months of bank and card statements. Categorize every transaction into high-level buckets: housing, food, transport, debt, fun, savings, other. You’re building a baseline, not judging yourself.

2. Define your monthly net income

Combine salary, freelance income, benefits, and any predictable transfers. Ignore irregular windfalls for now.

3. Set realistic targets per category

Use your baseline as a starting point. If food is $550, don’t instantly cut it to $250. Adjust in 5–20% steps. Include a buffer category for “unexpected” costs.

4. Allocate savings and debt priorities first

Decide how much goes to emergency savings and debt reduction before expanding lifestyle spending. Even $20–50 per month builds discipline and a safety cushion.

5. Choose your tracking tool

This can be a spreadsheet, a notebook, or one of the best budgeting apps for managing cash flow. The tool matters less than your consistency.

6. Track in real time (or weekly) and reconcile

Log expenses or sync the app, then once a week compare actual spending to planned amounts. Make live adjustments — reduce eating out if you overspent on entertainment, and so on.

7. Run a monthly review and refine

At month-end, check what worked and what broke. Update category limits. Your budget should evolve with your life and data, not stay frozen.

Practical Implementation Examples (Примеры реализации)

Example 1: Paycheck‑to‑Paycheck on a Low Income

Imagine someone earning a modest wage, feeling chronically behind. The key question is how to manage cash flow on a low income without burnout. The answer is ruthless clarity plus micro‑adjustments, not perfection.

They start by mapping inflows: two paychecks per month plus a small side gig. Outflows show a pattern: high delivery food costs, unused subscriptions, and overdraft fees. The first month of budgeting doesn’t change much behavior; it just reveals the leak points.

From there:

– They cancel underused subscriptions (instant fixed‑cost reduction).

– They set a strict weekly cash limit for food and transport.

– They schedule an automatic $25 transfer to savings on payday — a small “forced surplus.”

The result isn’t instant wealth. It’s the disappearance of overdrafts and the first tiny emergency fund. That’s practical progress.

Example 2: Using Apps Without Losing Control

Another person prefers technology. They download a couple of tools, compare features, and settle on one of the best budgeting apps for managing cash flow that can link to all their bank accounts. The app auto‑categorizes spending, but they don’t rely on it blindly.

They still:

– Manually check big transactions to avoid misclassification.

– Set custom alerts when any category hits 80% of its limit.

– Use the app’s cash-flow forecast to see whether next month’s large annual insurance bill is covered.

Here, the app is a decision-support system, not the decision-maker. The user keeps financial awareness and control.

Example 3: Analog “Envelope” Method in a Digital World

Physical envelopes still work very well for beginners who struggle with card overspending. Cash is withdrawn and split into labeled envelopes: Rent, Groceries, Transport, Fun, Misc. Once an envelope is empty, spending stops in that category.

A modern twist: “digital envelopes” in a banking app or multiple sub‑accounts. The logic stays identical; cash flow is partitioned into containers with specific purposes, reducing random leakage.

Frequent Misconceptions (Частые заблуждения)

Misconception 1: “Budgeting Is Only for People Who Already Have Money”

In reality, a budget is most critical when resources are tight. Without a plan, every unexpected expense triggers a cascade: overdrafts, credit card usage, late fees. For low or unstable incomes, budgeting is a risk‑management tool that stabilizes cash flow and reduces financial shocks.

Misconception 2: “A Budget Means No Fun”

A budget doesn’t eliminate fun; it quantifies it. Allocating, say, $150 per month to “Fun” means you can enjoy that amount guilt‑free and know you’re not sabotaging rent or savings. The absence of a plan often creates more stress and less sustainable enjoyment.

Misconception 3: “Once I Make a Budget, It Should Work Forever”

Personal finances are dynamic: incomes change, rents increase, kids appear, debts are paid off. A static budget quickly becomes obsolete. Think of your budget as a versioned document. Version 1.0 is your first attempt; each month you release a small update based on observed data.

Misconception 4: “Apps Automatically Fix My Money Problems”

Downloading a tool is not the same as changing behavior. Many people install a personal budget planner for beginners, connect their bank, glance at a few charts, and then ignore it. The real value comes from consistent interaction: reviewing categories, adjusting limits, and making decisions based on the information shown.

Misconception 5: “Budgeting Is Too Complicated for Non‑Experts”

The underlying math is addition and subtraction. The “technical” part is vocabulary — cash flow, fixed vs. variable costs, discretionary vs. nondiscretionary — and that can be learned quickly. Complexity appears only when people try to implement 12 systems at once. A lightweight structure is enough for most beginners.

From Theory to Action

If you’re just starting with budgeting for beginners, keep your initial setup deliberately simple:

– One view of your monthly net income

– A short list of categories (no more than 10)

– A single tool (spreadsheet, notebook, or app)

– A weekly 15‑minute check‑in

Over time, you can add layers: sinking funds for irregular expenses, targeted debt payoff strategies, or more granular tracking of business vs. personal spending. But the foundation is always your cash-flow awareness and the habit of planning ahead.

Put differently: your first goal is not to create the “perfect” system. It’s to build a reliable, working budget that tells you — in clear numbers — what you can safely spend, what you’re saving, and how your money is actually behaving month after month.