The real point of budgeting in 2025

Budgeting is not about punishment, spreadsheets or saying “no” to everything. In 2025, budgeting is better defined as a systematic allocation of cash inflows to planned and unplanned outflows over a fixed time horizon, with the goal of increasing net worth and reducing financial stress. That sounds technical, but in practice it just means: you tell your money where to go before it disappears. A proper budget links three layers: short‑term expenses (rent, food, bills), medium‑term goals (emergency fund, debt payoff, big purchases) and long‑term capital growth (investments). When these layers are synchronized, you get a repeatable process for building wealth incrementally instead of hoping for one big financial “win.”

Even if your income is modest or unstable, the mechanism is the same: control cash flow, then grow the surplus on purpose instead of by accident.

Key terms you’ll hear over and over

In personal finance, clarity on vocabulary is half the battle. Cash flow is the net result of money entering and leaving your accounts over a period, typically a month. Net worth is total assets (cash, investments, property) minus total liabilities (debts, unpaid bills, obligations). Savings rate is the percentage of your after‑tax income you keep instead of spending. Wealth, in a strict technical sense, is not income; it is the accumulation of productive assets that generate future cash flows with limited extra effort on your part. Understanding the difference between high income and high net worth will shape every decision you make around spending, saving and investing.

Think of these terms as the “units of measurement” in your money system; if you define them loosely, your results will be loose too.

How budgeting actually works under the hood

At a mechanical level, a budget is a constraint optimization problem: you have limited income and many competing uses for it. The “solution” is a set of percentage allocations that reflect your priorities and constraints. Many beginners start with frameworks like 50/30/20 (needs/wants/saving and debt payment), but treat those as starting parameters, not fixed law. A robust approach to how to start budgeting for beginners is to first map the *minimum viable lifestyle* (what you must spend to stay housed, fed and functional), then add layers for wants, buffers and investment contributions. The goal is to reach a positive cash flow margin that can be directed into wealth‑building instruments rather than short‑lived consumption.

In plain terms: give every dollar (or euro, etc.) a job before the month begins, then compare the plan with reality and adjust.

Text‑based diagram: your money pipeline

[Diagram: Money Flow Architecture]

Income → (Fixed Needs: rent, utilities, minimum debt) → (Variable Needs: groceries, transport) → (Wants: dining out, streaming, travel) → (Buffers: emergency fund, sinking funds) → (Wealth: investments, debt acceleration)

Visually, imagine a left‑to‑right pipe. Income enters from the left. Each section of pipe has a “valve” you can tighten or loosen: the more you restrict Wants and some Variable Needs, the more pressure you create in the Wealth section at the far right. Over months and years, that right‑hand section becomes more important than the rest because it starts throwing cash back at you in the form of dividends, interest and capital gains.

Your job is not to shut off fun forever; it’s to make sure the Wealth valve isn’t the smallest one in the system.

Incremental wealth vs “get rich quick”

Incremental wealth building means you aim for compound growth over long periods, driven by small but consistent positive cash flow and sensible investment returns. This is different from speculative wealth strategies (day trading, meme coins, lottery tickets) where the outcome is binary: big win or big loss. In a technical sense, incremental strategies optimize for *expected value* and *risk‑adjusted returns*, while speculative strategies optimize for *maximum upside* with minimal probability of success. A realistic step by step guide to building wealth focuses on repeatable behaviors: automatic transfers to savings and investment accounts, periodic rebalancing of a simple portfolio, and controlled spending drift as income rises.

You are building a machine, not buying a ticket.

First practical step: visibility over every unit of currency

Before you tweak categories or hunt for the best deal on groceries, you need measurement. For one full month, track every transaction—manual notes, bank exports, or apps, it doesn’t matter. From a technical standpoint this is data acquisition; without it, you’re optimizing blind. Tag each transaction by category and by “type”: fixed, variable, discretionary or investment. After 30 days, compute your total income, total outflows and cash flow surplus or deficit. This diagnostic baseline shows where your real levers are. Many people discover that subscriptions, food delivery and impulse online purchases quietly dominate their discretionary spending, while they thought “rent is the issue.”

Once you see the data, you can design rules that attack real bottlenecks instead of imagined ones.

Using apps without letting them run your life

Digital tools can automate 80% of the grunt work if you set them up correctly. The best budgeting apps to build savings in 2025 typically offer three functions: automatic import and categorization of transactions, rule‑based alerts (for overspending or big charges) and goal tracking (like “€500 emergency fund by July”). However, the app is only an interface to your behavior. Compared to a plain spreadsheet, apps excel at real‑time feedback and nudges, but they can also create a false sense of control if you never act on the reports. Think of them as the dashboard in a car: useful dials, but you’re still steering.

Pick one tool, learn it exactly enough for your needs, and avoid “app hopping,” which resets your data history and delays real progress.

Budgeting frameworks compared

There are several common architectures for personal budgets. The zero‑based budget assigns every unit of income to a category until nothing is left unallocated; this is precise and works well for irregular income but requires more attention. The percentage‑based budget (e.g., 60% needs, 20% wants, 20% saving/investing) is easier to maintain but less granular. The pay‑yourself‑first model moves savings and investment contributions out immediately after payday; the remaining balance is what you’re allowed to spend. From a systems viewpoint, pay‑yourself‑first behaves like an automatic firewall that protects your wealth‑building rate from lifestyle creep more effectively than most other structures.

In practice, many people combine them: pay yourself first, then allocate the rest using simple percentages and occasional category caps where you tend to overspend.

Example: from chaos to a simple architecture

Imagine someone earning $2,500 per month net, with no current system. After 30 days of tracking, they find $600 going to eating out and delivery, $200 to random online shopping, and only $50 to savings. By applying a hybrid model, they might automate $300 per month to savings and investments on payday, cap eating out at $300 and online shopping at $100. Now their forced savings rate jumps from 2% to 12%, solely by re‑routing flows, not by radical deprivation or higher income. Over a few years, those steady contributions become the core of their investment capital.

The structure does not have to be perfect; it only has to be consistent and survivable given your current lifestyle.

Building wealth on a low income: constraints and tactics

When money is tight, trade‑offs are harsher, but the logic stays the same. Effective personal finance tips to grow wealth on a low income focus on three axes: reducing fixed expenses, boosting small income streams and preventing expensive emergencies. On the cost side, co‑living arrangements, public transport instead of car ownership, and aggressive bill negotiation have disproportionate leverage. On the income side, even modest side work (freelance gigs, part‑time shifts, digital microtasks) can move your savings rate from 0% to 5–10%. Emergency avoidance involves insurance, preventive health care and a dedicated emergency fund that stops small crises from turning into high‑interest debt spirals.

You’re playing the same game as a high‑earner, just on a narrower board; precision and risk management matter more.

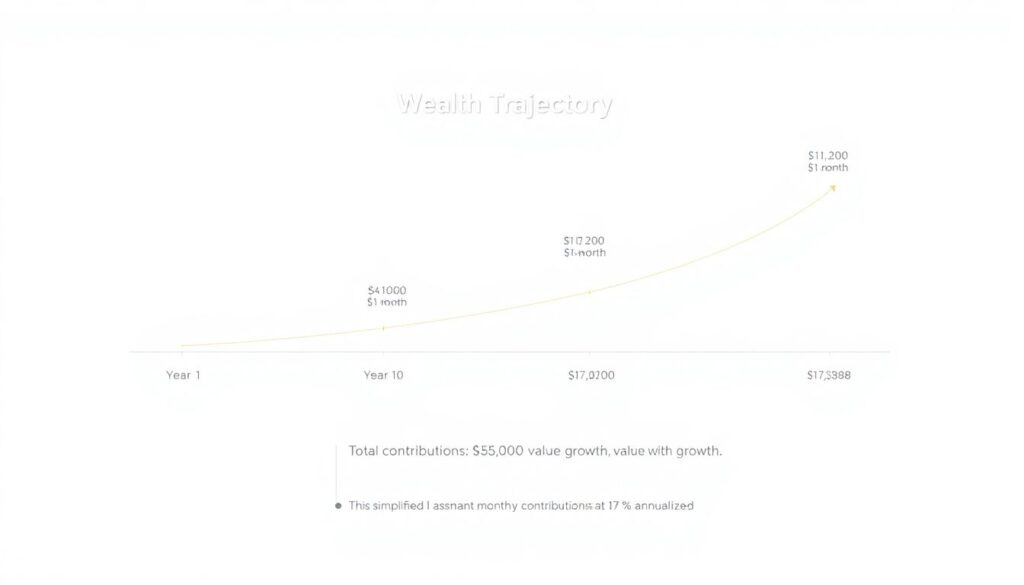

Text‑based diagram: compounding from small amounts

[Diagram: Wealth Trajectory]

Year 0: $0 invested, $0 annual growth

Year 1: $1,200 invested ($100/month), ~7% growth → ~$1,284

Year 5: Contributions $6,000, growth → ~$7,020

Year 10: Contributions $12,000, growth → ~$17,308

This simplified diagram assumes constant contributions and a 7% annualized return. The key observation: around year 8–10, growth on your prior contributions starts adding more than a single new monthly deposit. That inflection point arrives earlier if your savings rate is higher, and later if your spending absorbs all available cash. Budgeting is the lever that determines how quickly you reach the phase where money works harder than you do.

Even small, sustained contributions matter because they pull you across that threshold.

From saver to investor: the second phase of the journey

Once you’ve established a stable surplus and a basic emergency buffer (typically 3–6 months of essential expenses), incremental wealth building depends on your transition from simple saving to structured investing. Technically, this is where you convert cash reserves—which protect you from volatility—into risk assets that can outpace inflation. long term investing strategies for beginners favor diversified vehicles such as broad‑market index funds or low‑cost ETFs, held over multi‑year horizons with minimal trading. Your budget should now include a distinct line item for “investment contributions,” separate from general savings, with the understanding that this money is not for near‑term consumption or emergencies.

In other words, you graduate from just *not going backward* to actively *moving forward* on purpose.

Example allocation: bridging budget and portfolio

Consider someone with a $500 monthly surplus. A conservative but growth‑oriented split might be: $150 to emergency fund until it reaches a target, $300 to a diversified index fund and $50 to a specific goal like education or a future business. The budget enforces these flows: transfers execute automatically on payday, and regular spending is calibrated around the post‑transfer account balance. This link—budget categories feeding investment vehicles—is what transforms “I should invest more” into an actual, running process that continues even when you’re busy or distracted.

The details of each fund matter less than the consistency of contributions and the total fees you pay over time.

Technology’s role in 2025 and beyond

By 2025, personal finance tools are increasingly AI‑assisted. Many apps can forecast cash flow, categorize transactions with high accuracy and detect anomalies (like duplicate charges) automatically. Over the next five to ten years, we’re likely to see autonomous financial agents that execute micro‑decisions based on your policy rules: adjusting savings rates when your salary changes, rebalancing portfolios, or delaying non‑essential purchases when an unexpected bill hits. For beginners, this will blur the line between “budgeting” and “financial automation,” making how to start budgeting for beginners less about manual tracking and more about configuring guardrails and permissions.

The core skill will shift from data entry to policy design: defining what you want your money system to do under different conditions.

Forecast: how incremental wealth building will evolve

Expect three major shifts. First, real‑time personalization: tools will model your spending and income volatility to recommend bespoke savings rates and asset allocations, replacing one‑size rules like 50/30/20. Second, embedded investing: brokerage and budgeting functions will merge, so a single app can reroute unspent category balances into low‑risk funds automatically each month. Third, behavioral scaffolding: more apps will use nudge theory and gamification, rewarding consistent contributions and gently penalizing harmful behavior like repeated overdrafts. For those who understand the basics, these systems will amplify good habits; for those who don’t, they risk becoming black boxes.

That’s why even in 2030, basic literacy about cash flow, risk and compounding will still matter more than any specific tool.

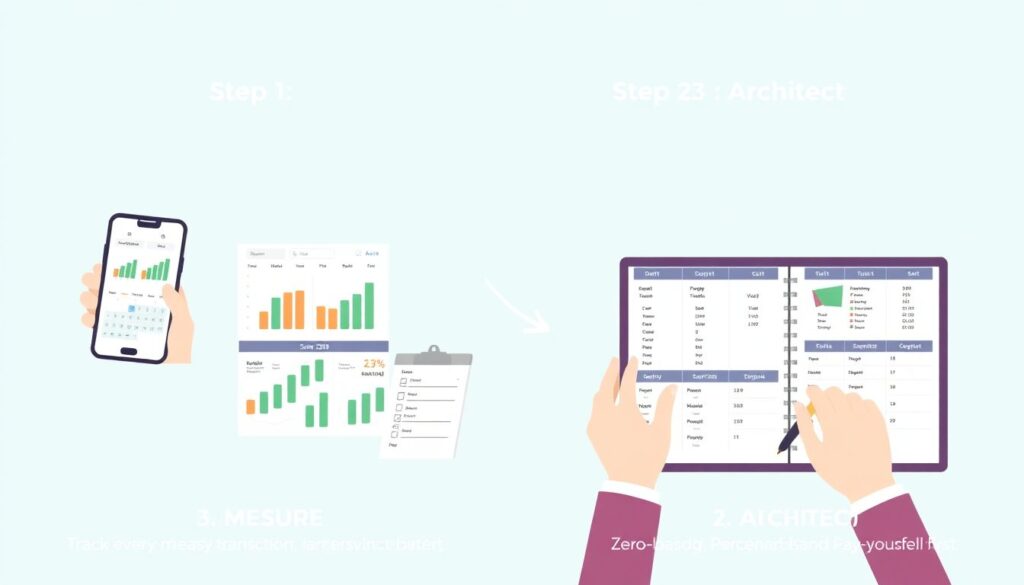

Putting it all together: a simple operational roadmap

Think of this as an operational, not motivational, sequence. First, measure: track every transaction for at least a month and calculate your true cash flow and savings rate. Second, architect: choose a budget framework (zero‑based, percentage‑based, or pay‑yourself‑first) and set clear category caps. Third, automate: schedule transfers so saving and investing happen by default, not by willpower at the end of the month. Fourth, upgrade: direct increasing portions of your surplus into diversified, long‑term assets as your emergency buffer solidifies. Throughout this step by step guide to building wealth, review monthly and refine quarterly so your system adapts to new incomes, goals and constraints.

Budgeting is no longer a static list of numbers; it’s a living protocol that steers your money toward your future self.

Last word: focus on systems, not perfection

You will overspend some months. Markets will dip. Jobs will change. A robust budget and wealth‑building setup is designed with that volatility in mind. Aim for a system where small mistakes don’t trigger catastrophic outcomes, where saving and investing resume automatically after disruptions, and where your net worth trend is up and to the right over multi‑year windows. The combination of clear definitions, simple diagrams of your money flow, deliberate comparisons of tools and strategies, and modest but regular examples of progress will keep you grounded when headlines and social media try to sell shortcuts.

In 2025 and beyond, incremental wealth isn’t about brilliance; it’s about building a boring, reliable engine and letting time do its work.