Why Budgeting in 2025 Is Less About Sacrifice and More About Control

In 2025, budgeting already moved far from the old stereotype of “counting every penny in a notebook and feeling guilty for coffee.” Today it’s closer to a control system: you decide what your money should do, instead of wondering where it went. With prices and subscription models changing faster than ever, a budget is like an operating manual for your cash flow. It doesn’t exist to punish you; it exists to align your spending with goals like travel, education, debt payoff or early retirement. Once you look at money as a tool, not as a source of stress or status, the whole process starts to feel more like strategy and less like restriction.

From Envelopes to Apps: A Short History of Budgeting

If you think budgeting is a modern invention, it’s not. Ancient Mesopotamian merchants already tracked grain and silver with clay tablets, essentially doing early “cash accounting.” In the 19th and early 20th century, households used paper envelopes labeled “rent,” “food,” “coal,” and physically divided cash. That envelope system is still used as a simple budgeting method to pay off debt, just in digital form. By the 1980s we saw personal finance software like Quicken; in the 2010s, apps started linking directly to bank accounts. Now, in 2025, algorithms can auto-categorize transactions, forecast upcoming bills, and even warn you when subscriptions quietly increase prices. The core idea hasn’t changed: track inflows and outflows so you can decide deliberately, not reactively.

Historical Context: Why Budgets Became Essential

Budgeting spikes in popularity when life gets financially unpredictable. After the 2008 crisis, people realized that “winging it” with money could be dangerous. The COVID-19 shock in 2020–2021 pushed this further: millions saw incomes drop while fixed expenses stayed. Search data showed global queries like “how to start a budget and save money” jump by more than 60% in some countries. By 2025, with inflation waves, gig work and remote jobs, personal finance feels more like managing a small business. Employers don’t guarantee stable careers, so the only real stability you can engineer comes from how you plan cash flow, build buffers and allocate to long-term goals. A personal budget became less a nerdy hobby and more basic self-defense.

Step Zero: Define What You Actually Want Money to Do

Before downloading tools or filling out a beginner budget template for monthly expenses, you need clarity on your targets. Vague wishes like “I want to save more” are useless in practice; concrete goals like “€5,000 emergency fund in 18 months” or “pay off $4,000 credit card by June next year” can be reverse‑engineered into a real plan. Think of money as an employee: if you don’t give it a job description and deadlines, it will wander off into random impulse purchases. Start with three categories: safety (emergency fund, insurance), progress (debt payoff, education, investments) and enjoyment (travel, hobbies, dining out). Assign rough numbers and deadlines to each, even if they feel imperfect. You can refine later; the key is to stop treating money as abstract and start treating it as a resource you deploy.

Technical block: Turning goals into numeric targets

Take one goal and translate it into a monthly allocation. Suppose you want a $3,000 emergency fund in 12 months. Calculation is simple: $3,000 ÷ 12 = $250 per month. If your net income is $2,500, that’s 10% of take‑home. Note that financial planners usually recommend an emergency fund of 3–6 months of core expenses; if your essentials are $1,500, the long‑term target is $4,500–9,000. For debt, prioritize high‑interest balances (often 18–25% APR on credit cards). If you owe $2,000 at 22% and pay only the minimum, payoff can stretch to many years with large interest cost. Using a structured plan with fixed monthly overpayment often cuts total interest by hundreds of dollars.

Cash Flow 101: Know Your Inflows and Outflows

Most first budgets fail not because the person is “bad with money,” but because they underestimate irregular and semi‑fixed costs. To build a personal budget planner for beginners that actually reflects reality, you need a three‑month snapshot of your finances. Pull bank and card statements for the last 90 days and categorize each transaction: housing, utilities, groceries, transport, debt payments, subscriptions, healthcare, discretionary. Irregular items like annual insurance, car repairs or gifts should be averaged monthly. For example, if you spent $600 on car maintenance over the past year, that’s $50 per month you should be reserving. This exercise often reveals that people underreport food and small digital purchases by 20–40%. Once you see the real picture, you can start adjusting, instead of building a fantasy budget that breaks within two weeks.

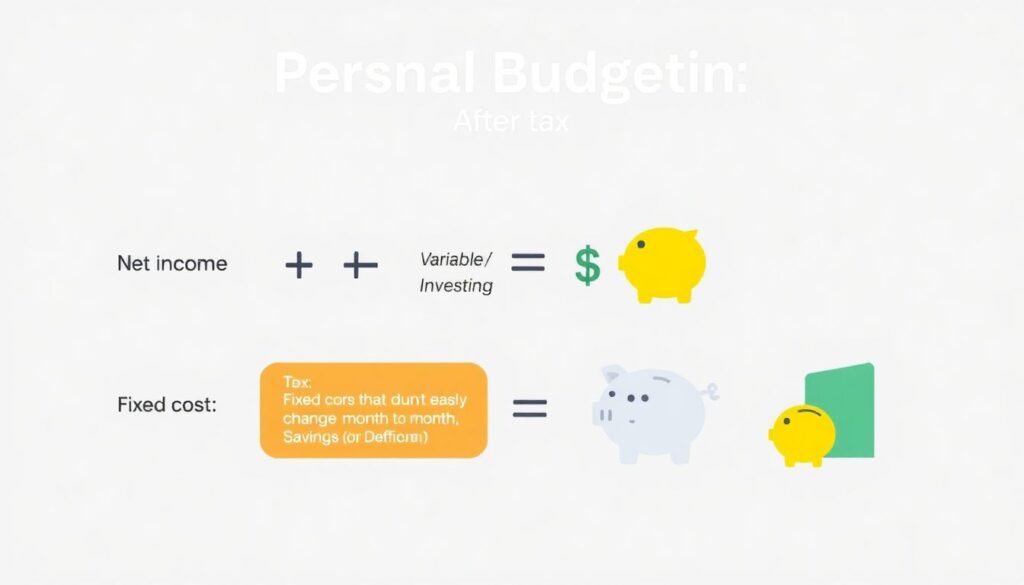

Technical block: Basic cash‑flow formula

At a minimum, your budget uses a simple identity: Net Income − Fixed Costs − Variable Costs − Savings/Investing = Surplus (or Deficit). Net income is after tax. Fixed costs are obligations that don’t easily change month to month (rent, minimum debt payments, insurance). Variable costs are flexible (groceries, dining, entertainment, transport to some degree). Savings and investments include emergency fund, retirement accounts, brokerage, sinking funds for big purchases. Aim for at least 10–20% of net income going to savings/investing once high‑interest debt is controlled. If you’re running a deficit, you have exactly three levers: raise income, cut costs, or extend time to reach goals. The math is simple; the behavioral change is the hard part.

Choosing a Simple Budgeting Method That You’ll Actually Use

People love to argue about the “best” system, but the effective one is the one you’ll stick to for at least six months. For absolute starters, I often suggest either a 50/30/20 rule or a zero‑based budget as a simple budgeting method to pay off debt and regain control. Under 50/30/20, about 50% of net income goes to needs, 30% to wants, 20% to saving and debt payoff. It’s an easy diagnostic: if your “needs” are eating 70%, you know housing or transport are too heavy. Zero‑based budgeting is stricter: every dollar is assigned a job before the month starts, so income minus planned spending equals zero. It’s powerful for people who feel money “slips through fingers,” though it needs more weekly check‑ins.

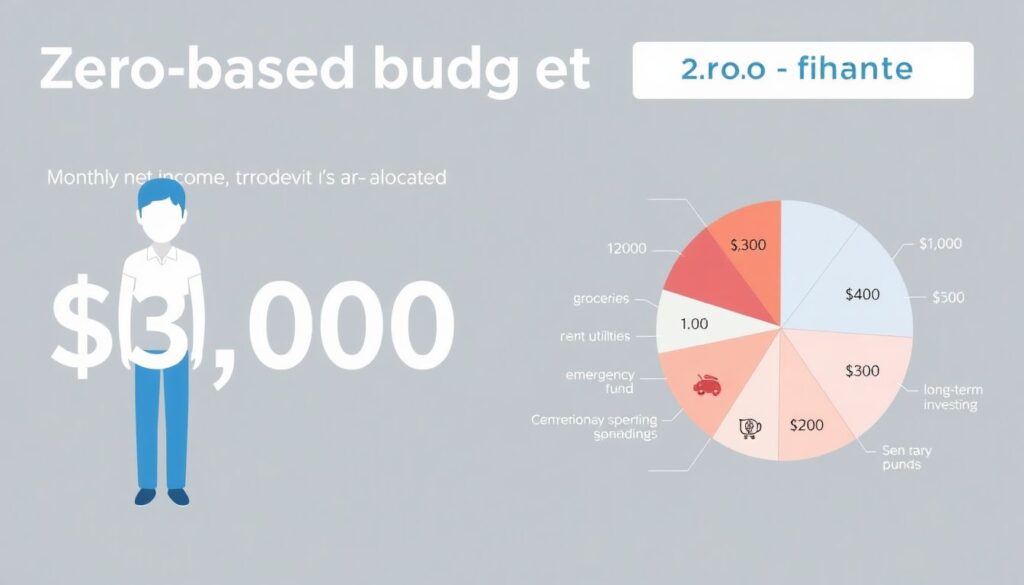

Technical block: Zero‑based setup in practice

Assume net income is $3,000. In a zero‑based model you pre‑allocate that entire sum. Example: $1,200 rent, $300 groceries, $150 utilities, $100 transport, $200 debt payments, $250 emergency fund, $200 long‑term investing, $200 sinking funds (car, gifts, travel), $200 discretionary, $200 “buffer” for small unplanned items. Total: $3,000, leaving zero unassigned. During the month, you track whether real spending aligns with these buckets. If you overspend on restaurants by $50, you must pull $50 from another category, like discretionary or buffer, not from “nowhere.” This structure makes trade‑offs transparent instead of letting you drift into overdraft or new debt.

Real‑Life Example: How a Beginner Budget Changes Behavior

Consider Anna, a 27‑year‑old designer earning about $3,200 after tax. She felt stuck: $1,000 on rent, student loan payments, plus random spending left her wondering “where did it go?” She set up a beginner budget template for monthly expenses using a simple spreadsheet and a phone app. After three months of tracking she discovered $380 per month pouring into food delivery, coffee and “small” Amazon orders. Instead of eliminating all of it, she capped those categories at $200 and re‑routed $180 into extra loan payments and an emergency fund. Within a year, she cleared a $2,000 high‑interest credit balance and built a $1,800 cash cushion. Nothing magical happened to her income; she just redirected money from low‑value habits to high‑priority goals she actually cared about.

Digital Tools: Let Apps Do the Boring Work

You don’t need software to budget, but in 2025 ignoring automation is like refusing to use navigation in a new city. The best budgeting apps for beginners handle transaction imports, categorization and trend analysis, so you spend mental energy on decisions, not data entry. Look for features like multi‑currency support if you travel, subscription tracking, goal buckets and alerts when spending exceeds your plan. Some apps implement envelope‑style budgeting by giving every dollar a virtual job right after payday. Others are more like dashboards, showing how your actual behavior compares to the plan. For people who hate spreadsheets, even a simple bank‑native analytics tool is far better than nothing. The key is to check in weekly for five to ten minutes, not just once a year when panic hits.

Technical block: Security and data considerations

When selecting a personal finance tool, check for bank‑level encryption (often 256‑bit), read their data‑sharing policy, and confirm whether they sell anonymized behavioral data. Many modern platforms use API‑based connections (e.g., Plaid‑style aggregators) instead of storing your login credentials directly, which is safer. Prefer tools that support two‑factor authentication and allow export of your data in CSV or similar formats. Also, keep in mind that some “free” apps monetize via promotions for credit products; take those recommendations as marketing, not neutral advice. From a risk management perspective, linking read‑only access to accounts is generally acceptable for most users, but you should still monitor for unusual activity and change passwords regularly.

Paper vs. Digital: How to Pick Your Personal Budget Planner

A personal budget planner for beginners can be as low‑tech as a notebook or as advanced as a multi‑device app. Paper has an underrated advantage: the act of handwriting expenses increases awareness and slows you down before impulse purchases. Digital tools, however, win on speed, automation and historical analysis. Freestyle‑minded people sometimes prefer a hybrid: planning and goals in a physical planner at the start of each month, tracking and adjustments in an app. The right choice depends on your temperament. If you already spend ten hours a day on screens, a physical planner might make budgeting feel more intentional. If you’re data‑driven and like charts, a digital dashboard with trend lines and category breakdowns can be more motivating.

Dealing with Debt: Using the Budget as an Offensive Weapon

Budgeting isn’t just about “stopping the bleeding”; it’s a way to attack debt strategically. Start by listing all debts with balances, interest rates and minimum payments. Then choose a payoff method: avalanche (highest rate first) or snowball (smallest balance first). Avalanche is mathematically optimal, but snowball creates quick psychological wins, which can matter more for long‑term adherence. Either way, your budget should identify a fixed extra amount—say $150 per month—dedicated specifically to the current target debt. This turns your budget into a deliberate repayment system, not just damage control. When one balance is cleared, you roll its entire payment into the next, creating a compounding effect in your favor instead of the bank’s.

Technical block: Example of a debt snowball

Suppose you have: $600 credit card at 23%, minimum $25; $1,500 store card at 19%, minimum $40; $4,000 student loan at 6%, minimum $80. You find $120 extra in your budget by trimming dining and subscriptions. Total extra debt payment is $120 + all minimums = $265. Under snowball, you first target the $600 card: pay $145 there ($25 + $120 extra), while paying only minimums on others. That card disappears in about five months. Then you redirect its $145 to the $1,500 card, now paying $185 on that ($40 + $145). Once that’s gone, all freed cash attacks the student loan. Over several years, this structure can reduce payoff time dramatically versus paying minimums, and total interest savings can reach four figures depending on rates and balances.

Common Beginner Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

New budgeters often set unrealistically tight numbers, like slashing groceries in half or banning all social spending. That usually backfires: life happens, guilt builds, and the whole system gets abandoned. A more sustainable approach is to start by just tracking for one month, then cutting 10–20% from overspent categories, not 70%. Another frequent error is forgetting “non‑monthly” costs—birthdays, annual services, car tax. A robust beginner budget template for monthly expenses includes sinking funds for these: small monthly contributions into labeled buckets so big bills don’t feel like emergencies. Finally, many people quit after one “bad” month. Treat your budget as a prototype; every month is a test run that teaches you something about your real behavior and your priorities.

Making Budgeting a Habit, Not a One‑Time Event

The real power of budgeting appears after repetition. A single month of tracking is like one gym session—you won’t see transformation. Build a routine: a 30‑minute “money date” before each month to plan, and ten‑minute weekly check‑ins to compare reality with your plan. Over time, patterns emerge: you realize winter utilities spike, or that you consistently underestimate travel. Adjust categories instead of forcing yourself into numbers that don’t match your life. In 6–12 months, you’ll likely see a clearer emergency fund, lower toxic debt and more deliberate spending. At that point, money anxiety usually drops noticeably, not because income necessarily grew, but because the system turned chaos into a controlled process aligned with your goals.

Using Money as a Tool: A Mindset Shift

Once you’ve run a budget for several cycles, you start to see money choices as design decisions, not moral verdicts. Want to work four days a week instead of five? Your budget can show what expenses must shrink or what income must rise. Dreaming of a sabbatical or moving cities? You can model scenarios with concrete numbers instead of vague hopes. By 2025 standards, financial volatility is normal—industries shift, automation changes jobs, and housing costs keep dancing. A working budget won’t eliminate uncertainty, but it turns you from a passive passenger into an active navigator. That’s ultimately what “budgeting for beginners” is about: learning to use your money like a tool that builds the life you want, rather than a force that constantly surprises you.